Politically Correct and Woke

Media use of culture war terms

New York Times columnist John McWhorter has recently explored how the use of “politically correct” and “woke” have evolved in American culture. His discussion illuminates important ebbs and flows of language change, noting that both have been “refashioned” as insults. Yet his analysis risks underemphasizing two critical factors in how the US public encounters such terms: the role of individuals in deliberately juicing the culture wars and the fact that mainstream media outlets only use terms once they become highly contested.

As McWhorter explains, in the mid-1980s and then in the early 2010s, politically correct and woke were popular on college campuses and among progressive activists. They signalled a sense of propriety—an intentional effort to “do no harm” and to support an array of policies and perspectives intended to uplift marginalized communities.

To understand how these terms migrated into the public eye, we gathered every article from 1981 through 2020 mentioning political correctness or wokeness from four national-audience newspapers: The New York Times, The Washington Post, The Wall Street Journal, and USA Today. Our analysis shows that these outlets largely ignored political correctness and wokeness during their initial phase of progressive endorsement. Only when they became contested—or openly mocked—did these terms regularly appear in the mainstream media.

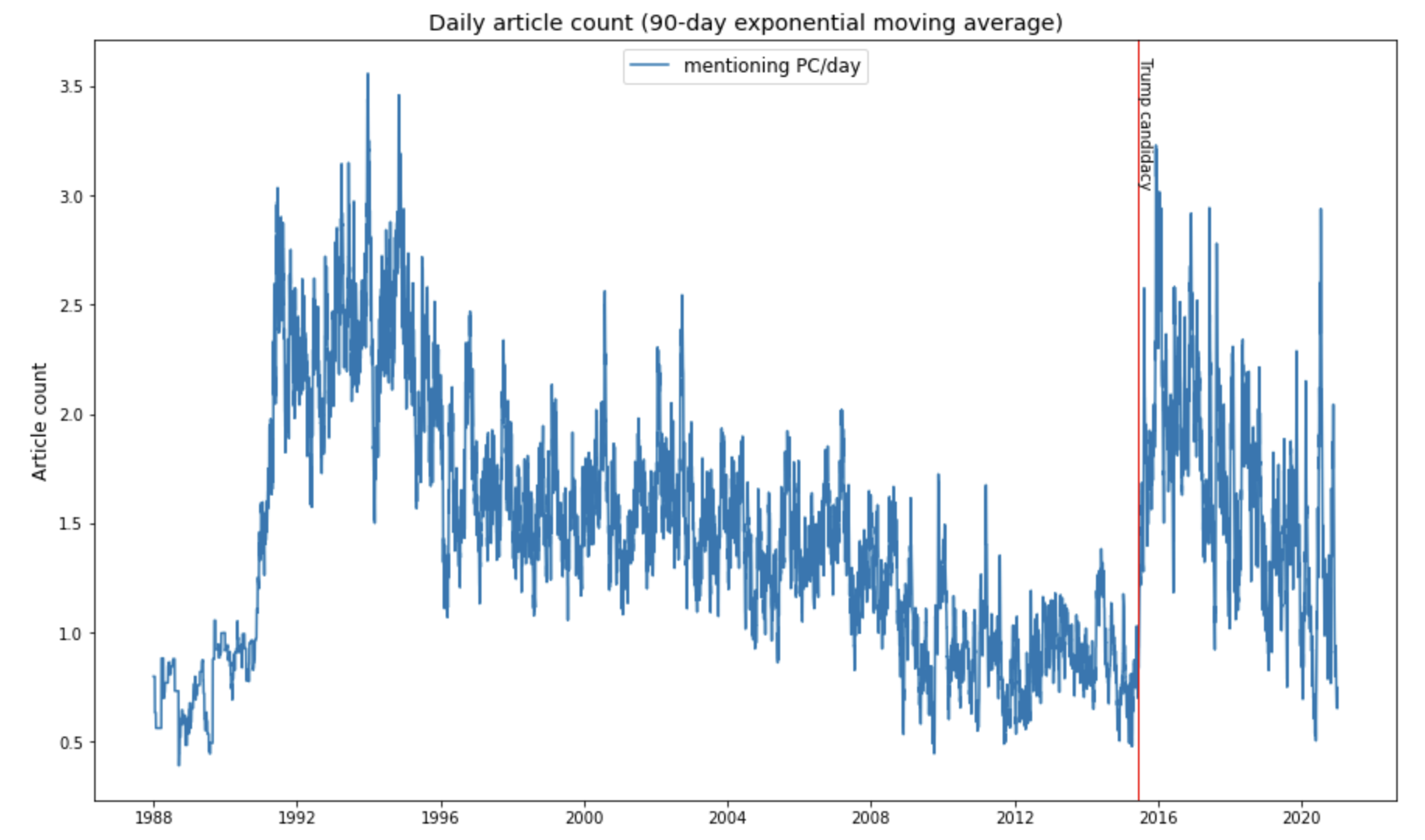

As we see below, stories touching on political correctness first emerged to a notable degree in the four outlets only in the 1990s. Political correctness appeared in 213 articles in the ten years between 1981 and 1990; then in over 600 articles in each of 1991 and 1992. Mentions tapered steadily between the mid-1990s and 2015, and then spiked again following Donald Trump’s gilded escalator announcement of his candidacy.

By the time these stories were a regular staple in newspapers, they were largely skeptical or even outright hostile to political correctness. An April 1991 Washington Post opinion piece by conservative author Dinesh D’Souza, for example, lamented “political correct orthodoxies” and called for universities to support “the articulation of widely differing views,” a sentiment all together too familiar thirty years later. A May 1991 New York Times article quoted President George H.W. Bush’s claim that political correctness “has ignited controversy across the land.” And in the heat of election season, a September 1992 letter to the editor of the Washington Post lauded former Republican presidential candidate Patrick Buchanan for articulating the view that affirmative action is “politically correct discrimination redirected against white Americans.”

Though discussions of political correctness were dying down in the 2000s, they spiked again in 2015. From just over 200 articles per year mentioning the term from 2010 through 2014, the number doubled to over 400 in 2015, and peaked at over 700 in 2016. The bulk of these covered Donald Trump and the culture war politics his candidacy unleashed.

An article from July 2015, for example, quotes a supporter lauding Trump as saying “what everyone else thinks but is afraid to say because they want to be politically correct.” In response to questions about some of his own “incendiary comments,” Trump asserted in an August 2015 Republican debate that he did not “have time for total political correctness.”

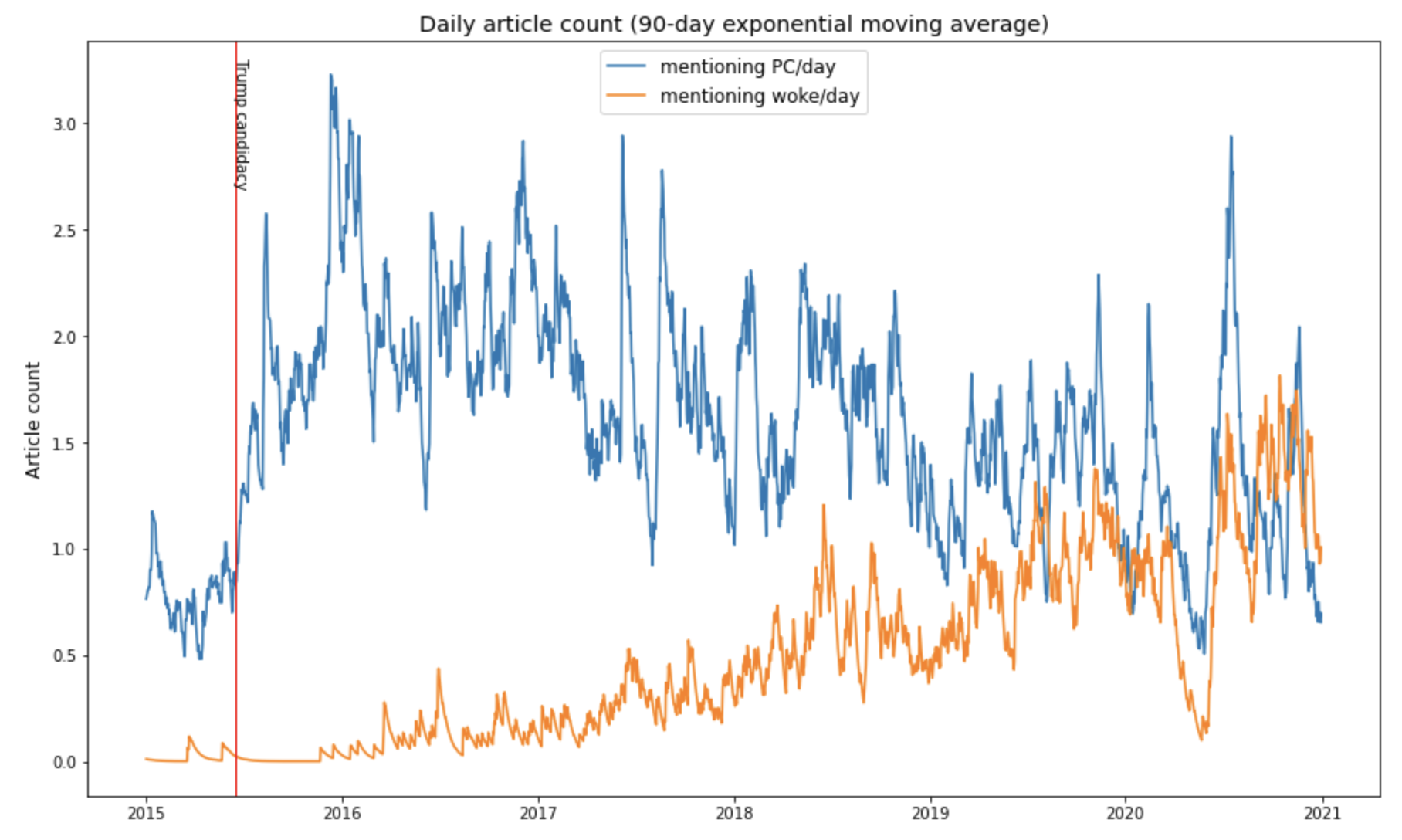

Mainstream national newspapers thus lagged the early use of political correctness, and introduced it in light of cultural or political friction associated with the term. We see a similar pattern for “wokeness.” The following figure includes the average article count for political correctness from 2015 through the end of 2020 as a baseline, adding a line for wokeness terms for comparison. While McWhorter dates the progressive embrace of “woke” to 2012, there was no coverage in our four newspapers until 2015 that referred to wokeness.

As woke made inroads into the mainstream media in 2016 and eventually became as common as political correctness, its use was also largely pejorative. Some of the articles captured a transition among Republicans from their prior pillorying of political correctness to decrying “the woke mob of liberals.” Others noted concerns among the “moderates and liberals” themselves, who were purportedly “keeping their heads down, so they will not get bitten off by woke mobs.”

Of course, not all uses of woke have been out-and-out negative. Some articles offered definitions of woke, including a 2017 David Brooks gloss that to be woke is “to be radically aware and justifiably paranoid,” while a letter to the editor in the Washington Post playfully asks for more “eye-opening” stories “so voters can stay woke.” But much more common were lines suggesting the limits of wokeness, such as a 2017 Lindy West column observing that “in most of America, including wide swaths of lefty progressivism, it is still not cool to be ‘woke.’ It is obnoxious.”

McWhorter is right that the meanings of politically correct and woke are bound to evolve. Our analysis suggests that political actors and journalists are not just reflecting the environment around them, but also play an active role bringing these terms to public audiences and amplifying their divisive nature. Societal changes in language are the product of strategic and editorial choices that affect how we see the world around us.

-Erik Bleich

Methodological note: We collected 15,206 articles mentioning the terms politically correct, political correctness, woke, wokeness, wokeism, or wokism in the New York Times, the Washington Post, the Wall Street Journal, and USA Today from January 1, 1981 through December 31, 2020. (Approximately 5 articles per year are variants of “to wake”; these were not filtered out but do not affect our analyses or conclusions.) For additional information regarding our methods, see here. Photo credit: Heterodox Academy.