Immigration Rhetoric Goes Dark

The rise of fear in coverage about migrants

The first 100 days of the new Trump administration upended US immigration policy through sweeping executive orders, lawsuits, and an aggressive campaign of raids, detentions, and deportations. Polls show that a majority of Americans support stronger border enforcement – a sentiment undoubtedly shaped at least in part by how media outlets frame immigration. This framing has changed dramatically since Trump first emerged on the political scene, with coverage not only including standard reporting on immigration policy but increasingly emphasizing fear-based narratives of threat, criminality, and violence.

How did we get here? When Trump launched his presidential campaign in June 2015, he shocked the political establishment with rhetoric that would become his trademark: “When Mexico sends its people, they’re not sending their best… They’re sending people that have lots of problems, and they’re bringing those problems with us. They’re bringing drugs. They’re bringing crime. They’re rapists. And some, I assume, are good people.” The inflammatory tone from Trump only escalated after that, raising a critical question: To what extent did Trump’s language reshape how mainstream media discussed immigration?

To understand the rising use of what some have called “dehumanizing” language about migrants and whether Trump facilitated its growth in the media, we analyzed ten years of newspaper coverage, assembling all 95,549 stories mentioning “immigration” or “immigrant” from 2015 to 2024 in The New York Times, The Washington Post, and The Wall Street Journal. This reveals a dramatic transformation in how immigration was discussed in mainstream media, particularly after Trump’s 2016 election victory.

We tracked eleven of the most negative terms associated with immigration coverage today, ranging from associations with violence (rape, terrorist, murderer, carnage) to criminality (drug dealer, crime, gang, fentanyl) to emotive threat imagery (flood, invasion, animal). The data shows a clear inflection point following Trump’s election in 2016. From 2015 to 2016, most negative terminology saw modest increases as Trump’s campaign gained momentum. However, the real surge came after his election, with the use of all negative terms peaking in 2018.

In 2015, the eleven terms appeared 8,438 times in immigration coverage. By 2018, mentions more than doubled to 19,589. This dramatic shift demonstrates how quickly and thoroughly political rhetoric can reshape media discourse on complex issues.

The Trump presidency had a clear impact on this transformation. The spike in 2018 coincided with the implementation of the “zero tolerance” border policy in April of that year, which mandated the prosecution of all adults illegally crossing the border and led to thousands of family separations. The response included mass protests, such as the June “Families Belong Together” rallies, and subsequent court rulings which kept the issue in the media spotlight. Additionally, immigration became a central issue for Republicans in the 2018 midterm elections with candidates frequently emphasizing border security and using inflammatory rhetoric to energize their voter base.

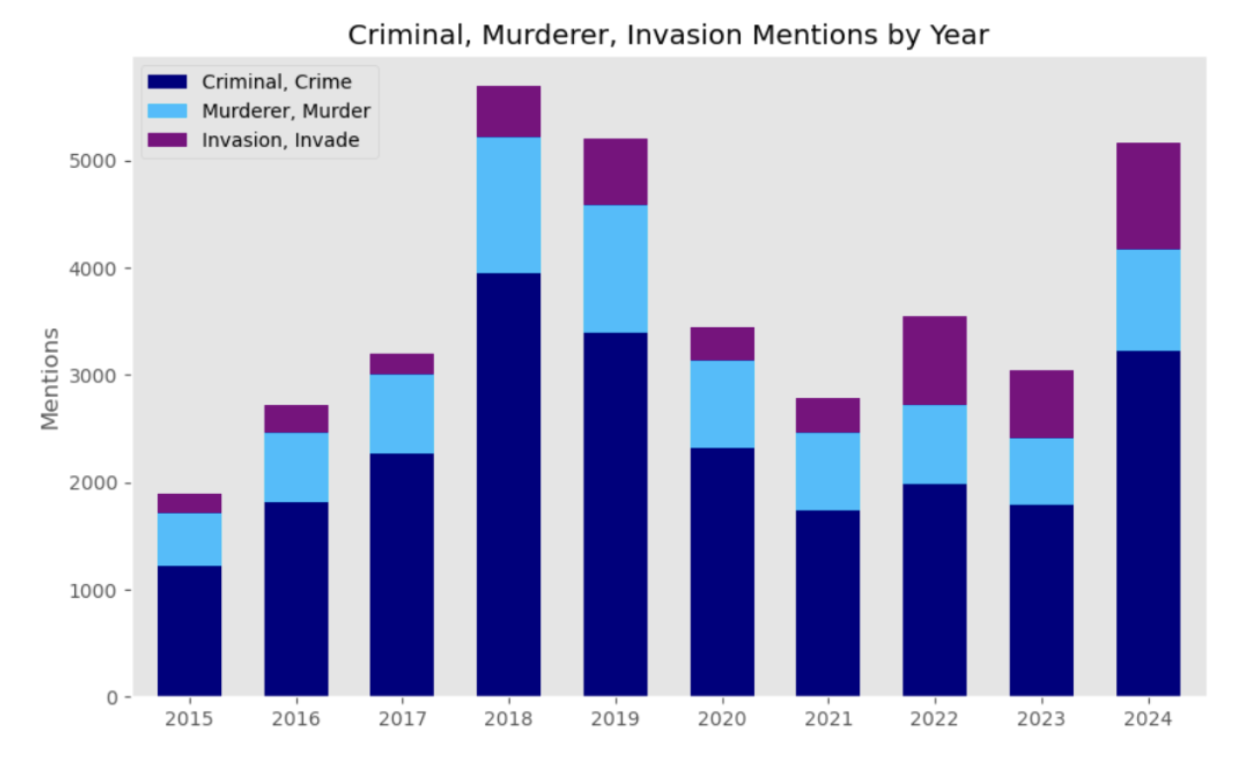

We focus on three key terms to tell this story: criminal/crime, murderer/murder, and invasion/invade. Each represents a distinct kind of fear-based rhetoric: immigrants as a threat of criminality (criminal), threat of violence (murderer), and an emotive threat (invasion). Together, their usage shifted discourse toward fear and security concerns.

Perhaps no connection has been more aggressively cultivated in recent years than the link between immigration and crime. “Criminal” appeared 13,704 times across all three newspapers from 2015 to 2024 – just second behind “crime” with 15,626 mentions. Our analysis shows that over those ten years, use of “criminal” surged 161%, while “crime” nearly tripled.

The mentions of “murder” or “murderer” also jumped between 2015 and 2018, reflecting an increasing association between immigration and violence – despite research showing immigrants commit crimes at lower rates than native born citizens. Simultaneously, the framing of immigration as an “invasion” more than doubled in the same period. By 2022, “invasion” or “invade” had skyrocketed to more than five times the 2015 levels. The persistent linkage has helped normalize a narrative that migrants are primarily threats to public safety rather than contributors to American communities.

The pattern is telling. Mentions of all three terms display massive spikes in 2018-2019, coinciding with Trump’s early immigration policy initiatives. There was a modest decline in inflammatory language during the Biden administration (2021-2024), but importantly, usage never returned to pre-2016 levels. The recent surge in 2024 suggests this rhetoric has become a permanent feature of immigration discourse and is likely to rise even more with Trump back in the Oval Office.

Our findings reveal a troubling amplification effect: as Trump’s provocative rhetoric became part of the national conversation, media outlets found themselves compelled to engage with and repeat these characterizations, even when attempting to fact-check or debunk them. This created a cycle where dehumanizing terminology became more prevalent in headlines and articles, threat narratives gained prominence over policy discussions, and even highly incendiary terms like “rapist,” “carnage,” and “gang member” became normalized among politicians and in public discourse.

The shift went beyond simply introducing new terminology to the immigration debate – it fundamentally reshaped how the media covered the topic. Even straightforward policy reporting now often engaged with assertions about criminality and invasion, further normalizing extreme language in mainstream coverage. As the country grapples with Trump’s new immigration policies, understanding the media’s framing of the issue reveals how the media not only reports on our national conversation, but also transforms the perception of who is allowed to belong in America.

—Ting Cui and Eva Janairo

Methodological note: We examined all 95,549 articles containing “immigration,” “immigrant,” or “immigrants” published between January 1, 2015 and December 31, 2024 in The New York Times, The Washington Post, and The Wall Street Journal. We tagged articles for eleven words and their plurals and variants: “gang,” “rape,” “terrorist,” “murder,” “carnage,” “drug dealer,” “fentanyl,” “crime,” “invasion,” “flood,” and “animal.” For additional information regarding our methods, see here. Photo credit: Nick Ut/Getty Images via Vox.